Ancient Persian Engineers Made Their Own Freezers That Kept Ice Cold Graphic © todaysfunfact.com. Background photos: Wikipedia 1, Wikipedia 2, lic. under Creative Commons 3.0

Refrigeration is an amenity that most of us heavily rely on today. But while the modern freezer sitting in your kitchen is a few decades old, the concept of refrigeration has been around for over 2,000 years.

It’s believed that ancient Persians in the Iranian desert collected ice from nearby mountains during colder months and used it for food storage, making frozen desserts, and as a luxury item during hot summers.

And while this was nothing novel—with records suggesting Romans, Greeks, and Chinese harvested ice as early as 1,000 BC—the Persians had a significant challenge on their hands: the hot, dry desert climate of Iran.

But as the saying goes, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” And invent the Persians did. By 400 BCE, their engineers had designed and perfected an advanced mechanism of storing harvested ice and freezing water to make more in a structure known as a Yakhchal (ice-pit).

The Ingenious Structure Of The Yakchal

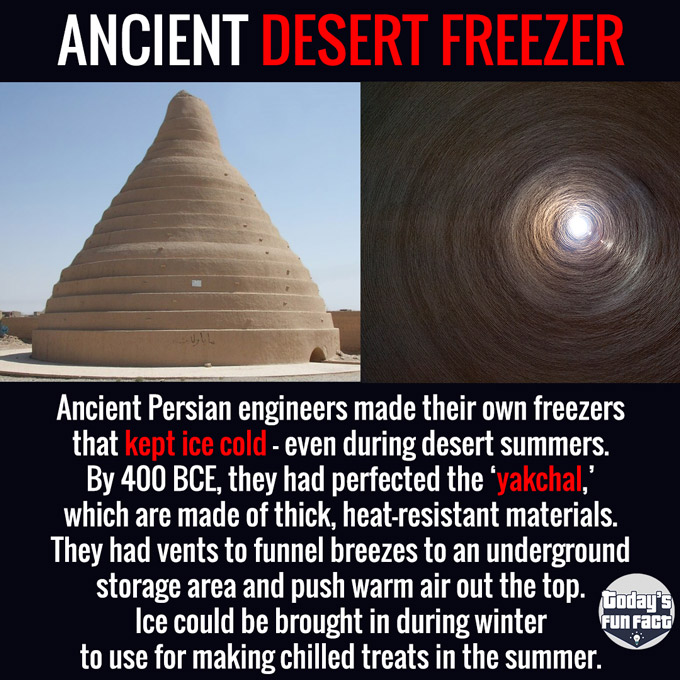

A Yakhchal is a towering dome (sometimes 60 feet aboveground) made of thick mud-brick walls and deep underground storage spaces (up to 5000 cubic meters).

The walls are designed for insulation, as evidenced by their thickness (sometimes as thick as 2 meters) and the use of a special watertight mortar (sarooj) made from ash, goat hair, lime, egg whites, clay, and sand.

The underground spaces have access to a qanat (aqueduct) that channels water to the Yakhchal for freezing. The structure also had windcatchers at the base of the dome, allowing cold wind to gush in.

Ancient Yakhchals were so well built that some of them still stand today.

Yakchal Mechanism of Action

The inside of a Yakhchal is significantly cooler than its surroundings, thanks to clever positioning for optimal radiative cooling and low desert humidity.

Cold air pours from entry points at the dome’s base, forcing warmer air through an opening at the top, which pulls more cool air from the base. And when the desert temperature hits its characteristics lows at night, water is channeled from a qanat for cooling.

This is the layman’s description. But a peek into the system’s intricacies reveals an impressively innovative mechanism that fully leverages the tides of nature. It’s an engineering masterclass.

Could we borrow a thing or two about sustainability from the genius of the ancient Persians? I think so.